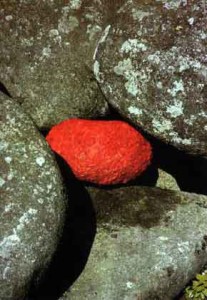

Sidobre, France is the location of Europe’s largest granite plateau and the site of Peyro Clabado – a place where a large boulder seems to defy gravity in the way it is perched atop a smaller stone. Sidobre was also the location of a piece of art that can be seen now only through photographs – because it ceased to exist long ago. The British artist Andy Goldsworthy found a stone wedged between larger boulders and adhered poppy petals onto its surface with water. In the photographs, the stone glows among the gray mammoths that surround it. It looks molten, alive, almost heart-shaped. I do not know how long it remained in this completed state, but can only imagine it would have been washed away with the next rain, or perhaps it didn’t even last that long. Goldsworthy has other compelling ephemeral art: a spiral of ice sculpted around a tree made from icicles found on a cold morning that would melt in the afternoon sun; a wave-like bridge of branches that would soon succumb to the current of a river.

Sidobre, France is the location of Europe’s largest granite plateau and the site of Peyro Clabado – a place where a large boulder seems to defy gravity in the way it is perched atop a smaller stone. Sidobre was also the location of a piece of art that can be seen now only through photographs – because it ceased to exist long ago. The British artist Andy Goldsworthy found a stone wedged between larger boulders and adhered poppy petals onto its surface with water. In the photographs, the stone glows among the gray mammoths that surround it. It looks molten, alive, almost heart-shaped. I do not know how long it remained in this completed state, but can only imagine it would have been washed away with the next rain, or perhaps it didn’t even last that long. Goldsworthy has other compelling ephemeral art: a spiral of ice sculpted around a tree made from icicles found on a cold morning that would melt in the afternoon sun; a wave-like bridge of branches that would soon succumb to the current of a river.

I came across a radio interview of Goldsworthy by Terry Gross during a week when I was playing music by Sibelius. The descriptions of his icy creations seemed to emphasize what I heard in Sibelius – a sort of minimalist, frozen world, but one that contained a love for what can be found in the soul of a particular landscape.

But as I’ve contemplated these images over a longer period of time, and as world events continue to unfold in ways that constantly challenge my hope in our collective future, my connection to his work has deepened. It feels like a reminder of the ever-present potential within a person: resourcefulness; awareness; the ability to see possibility and beauty in seemingly mundane surroundings; the ability to create from whatever the day contains. I feel my own very ephemeral life could be enriched if only I could live the way his art is created.

As a member of modern American society, there is a sense of needing to actively combat the inundation of distraction and noise if I do not want myself or my family to be consumed by it. Life is always in motion. Amplification, flashing lights, video screens, constant blips of information are everywhere. How does one make space for something meaningful to be created, or for the events of life to be metabolized? How does a modern person do something other than get from one moment to the next, each day a series of obstacles to overcome?

Andy Goldsworthy’s sculptures feel like an antidote to the noise around me, and I feel the possibility of my own profession to be an antidote as well. Classical music, which organizes nature sonically, offers a place of expression and connection for those who create it and those who hear it. Goldsworthy’s sculptures or a musical performance may only last for a period of time, but the effect of deeply experiencing something skillfully done, beautifully organized, created from awareness and connection to life, echoes far beyond the fleeting moment.