One of the great joys of my musical life is hearing the perspectives of artists who work in other fields. Painters, dancers, writers and actors have all enriched my own musical path. Recently, my exploration has happily brought me to the theater – an area where my expertise is limited to roles in childhood Christmas plays and a high school drama class in which I screamed bloody murder during an improv exercise – because that’s all I could think to do. I am not a good actor, nor can I tell a good story or even a decent joke, but, like most of us, I am captivated by what happens when great actors act.

A few weeks ago, expression in music (of both the underdone and overdone varieties) seemed to be a constant theme. At the same time I was struggling to help a couple young chamber music groups to understand and connect with music from the Renaissance, an era less familiar to them than others.

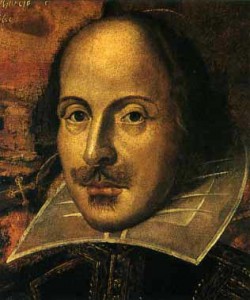

This is when I stumbled across a piece in the New York Times by Charles Isherwood entitled “What Makes a Great Shakespearian?” He begins by stating how one identifies a great performance of Shakespeare. He says he knows it’s great when “the language no longer feels remote, when the humanity of the actor and the character seem indivisible, when the emotion being expressed is no longer veiled by poetic phrasing but revealed by it, creating a shock of recognition in your own heart.”

This is when I stumbled across a piece in the New York Times by Charles Isherwood entitled “What Makes a Great Shakespearian?” He begins by stating how one identifies a great performance of Shakespeare. He says he knows it’s great when “the language no longer feels remote, when the humanity of the actor and the character seem indivisible, when the emotion being expressed is no longer veiled by poetic phrasing but revealed by it, creating a shock of recognition in your own heart.”

This statement itself created a shock of recognition in me, articulating exactly how I feel when listening to a great musical performance, no matter the era. I am not distracted by the musical language (whether ancient or written yesterday) or by any affect of the performer. I can hear the music speak and it just feels right.

Isherwood, in his article, went on to say that, in thinking about the qualities of a great Shakespearean performance, he dug out an old series in his possession called “Playing Shakespeare” by John Barton of the Royal Shakespeare Company. He explains that Barton believes the answer to the question of how to “play Shakespeare” lies in Shakespeare’s own text, in the form of direction that Hamlet gives to his players. He quotes the speech in part:

“Suit the action to the word, the word to the action, with this special observance, that you o’erstep not the modesty of nature. For anything so o’erdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end both at the first and now, was and is, to hold as ‘twere, the mirror up to nature.”

I decided to find “Playing Shakespeare” and experience it for myself, and I encourage anyone interested to do the same. The first seven minutes alone are jam-packed with extraordinary insight (and more of Hamlet’s speech) into how to begin to approach seemingly remote, daunting material both as an actor and an audience member. Incidentally, watching Ian McKellan, Patrick Stewart and the other very fine actors on the roster read lines and perform scenes in this casual masterclass setting is riveting, as is the conversation between them and Mr. Barton.

As the masterclass continues, it becomes clear that the question of how to help the audience make that leap over time and place is intimately linked to expression. Barton talks extensively about the dichotomy of naturalistic text and heightened text in Shakespeare as well as the natural (casual) ways that lines can be delivered versus the stylized ways. He shows (through the actors on stage with him) several examples of both overly-natural and overly-stylized treatments of both kinds of text, and demonstrates just how powerful it is when the right balance is struck.

At the same time Barton is careful to point out that there is no one best interpretation and that very fine actors and directors passionately disagree on many points. It is, however, important to do the investigative and exploratory work into the details of the text and the characters.

The questions raised by Isherwood and by Barton are not questions of how to reach a general public completely uninitiated or uninterested in Shakespeare, but rather, an investigation of what makes a truly great Shakespearean performance for the theater-going public. For us in classical music, rather than helping us to address the issues of cultivating new audiences and increase the “relevance” to newcomers to music, these points are most illuminating for those of us who are already dedicated to the art form. Perhaps some of the correlations to be made are: to serve the music and our audiences by looking deeply, being intentional, and understanding our role; having a vivid idea of the character and colors we want to communicate; to not get caught up in the cheap trick of over-emoting or distorting for sheer effect. (How easy it is to put the music into our service rather than the other way around.)

It also reminds me, despite the pressure to “make progress” and get through material, to not neglect the passing on of this deep, investigative approach to exploring and performing music that makes music-making (and listening to music) such a wonderful life-long pursuit. Passed along from music lover to fellow music lover, from teacher to student, it is what will keep our art form truly vibrant.

When I think about the musical qualities I strive for, and what I hope my students will incorporate into their own approach, Isherwood once again sums it up for me so eloquently in a later article (“Your Favorite Shakespeare Performances”) responding to readers’ submissions. Among his own favorites were several productions with Judi Dench. He remembers, “her performances were marked by a clarity of thought, a simplicity of speech and a warmth of humanity that I still recall with wonder.”

Clarity of thought. Simplicity of speech. Warmth of humanity.

How perfectly beautiful. What more could anyone want from music – or from life?