There was, once upon a time, a period of my life that was quite turbulent, or at least it felt quite turbulent to me at the time. It felt as though whatever I was going through had never happened before in the history of humankind. But my mother, in her wisdom, gently said to me, “there’s nothing new under the sun,” quoting from the first chapter of Ecclesiastes. I don’t think she said this to downplay what I was feeling, but rather, to help me understand that we all share in this experience of living on earth and to take comfort in knowing that what I was feeling and thinking had been felt and thought before – that someone had lived through (and survived) what I was living through. This is, after all, the reason we read (or should read) the great stories of humanity, why we study history, and why remembering is important. When these stories are lost, forgotten, or erased, we lose something of ourselves. And we lose an opportunity to think and act with generations of experiences (both the good and the bad) behind our actions, rather than with only our limited lives and perspectives as guidance.

There was, once upon a time, a period of my life that was quite turbulent, or at least it felt quite turbulent to me at the time. It felt as though whatever I was going through had never happened before in the history of humankind. But my mother, in her wisdom, gently said to me, “there’s nothing new under the sun,” quoting from the first chapter of Ecclesiastes. I don’t think she said this to downplay what I was feeling, but rather, to help me understand that we all share in this experience of living on earth and to take comfort in knowing that what I was feeling and thinking had been felt and thought before – that someone had lived through (and survived) what I was living through. This is, after all, the reason we read (or should read) the great stories of humanity, why we study history, and why remembering is important. When these stories are lost, forgotten, or erased, we lose something of ourselves. And we lose an opportunity to think and act with generations of experiences (both the good and the bad) behind our actions, rather than with only our limited lives and perspectives as guidance.

Yet I still find myself alternating between feeling that the world is falling apart in a way that it never has fallen apart before, and thinking that, well, it’s just falling apart in new ways. Or perhaps it isn’t falling apart. Perhaps the world is merely suspended in an ongoing cycle of decay and new growth, just as I am keenly aware of my own new ways of falling apart as I age, even as other aspects of life are constantly enriched and ever growing. I am suspended and spinning. Losing some things, gaining others.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the idea of “suspension” recently as I’ve had to put down my horn because of an injury I sustained back in May that has refused to heal the way I hoped it would. It became clear last month that the only thing to do was to stop playing for a while, give my body time and space – and to surrender to the idea that there IS time and there IS space for all of this. So, I feel myself completely suspended and without certainty. I don’t mean to be melodramatic. It is, after all, just a horn. Not a body part, not a loved one. But at the same time, I can’t deny that this is what I have worked for most in my life, what I’ve poured myself, my time, my dreams, my resources into, and it is unsettling to feel somewhat stripped of that identity for a while. I have every reason to believe that I will recover, but I would be lying if I said there is no voice inside that sometimes asks “what if it doesn’t come back?” or “what if I’m never quite the same?”

At the same time, it is also true to say that I am depleted from the efforts of the summer and early fall, when I tried to rebuild from this injury that had never quite healed in the first place, and there is a certain amount of relief in thinking of other things. And so, I sit and do projects with my son. We are crocheting together these days and folding origami cranes and ninja stars (his favorite). I go for walks each day, feeling myself simply as a person walking, rather than as someone on a mission. I have my wonderful students to teach, who themselves teach me so much.

One of my students recently said to me that she felt she had so much catching up to do. I understood why she felt this way, as this is how I often feel. But what if we changed the metaphor? What if we recognize that, no matter where we are in life, we always will feel a certain amount of incompleteness. There will always be something needing to be done. It’s the nature of living. What if I embrace my own unique path, embrace my own pace, and find a place to rest, even while suspended in midair?

I think often of the words of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, given to me by a friend and mentor during another unsettled time of my life. I will leave them here for you – and for myself. Even if the religious language does not resonate with you, perhaps the idea of the last two lines will infuse you (as they do me) with a feeling of being at home, even within a state of flux and uncertainty, and help you to “accept the anxiety of feeling yourself in suspense and incomplete.”

Patient Trust

Above all, trust in the slow work of God.

We are quite naturally impatient in everything

to reach the end without delay.

We should like to skip the intermediate stages.

We are impatient of being on the way to something

unknown, something new.

And yet it is the law of all progress

that is made by passing through

some stages of instability –

and that it may take a very long time.

And so I think it is with you;

your ideas mature gradually – let them grow,

let them shape themselves, without undue haste.

Don’t try to force them on,

as though you could be today what time

(that is to say, grace and circumstances

acting on your own good will)

will make of you tomorrow.

Only God could say what this new spirit

gradually forming within you will be.

Give our Lord the benefit of believing

that his hand is leading you,

and accept the anxiety of feeling yourself

in suspense and incomplete.

-Peirre Teilhard de Chardin, SJ

For those of you following the story of Baset, the young Afghan trumpet player that my husband has been mentoring, it has been a whirlwind of activity for him recently. Baset graduated from Interlochen Academy of the Arts in May, an accomplishment that was a mere dream two years ago as a student in Kabul. He received a full scholarship to the University of Kansas, but needed to raise the money for four years’ worth of living expenses and incidentals. Since his new

For those of you following the story of Baset, the young Afghan trumpet player that my husband has been mentoring, it has been a whirlwind of activity for him recently. Baset graduated from Interlochen Academy of the Arts in May, an accomplishment that was a mere dream two years ago as a student in Kabul. He received a full scholarship to the University of Kansas, but needed to raise the money for four years’ worth of living expenses and incidentals. Since his new  “It is not a requiem to console the living. Sometimes it does not even help the dead to sleep soundly.” – The Times

“It is not a requiem to console the living. Sometimes it does not even help the dead to sleep soundly.” – The Times As it turns out, it was written by Mimi Dixon, maiden name Still, daughter of the late Ray Still, principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty years (1953-1993). In this moving essay, she writes about her father, his last days (he died in 2014), the book they were writing together, and her own battle with leukemia. The breath itself is a point of meditation, as well as a device for exploring the powerful presence of her father. Wind and breath weave in and out of stories about her father’s approach to playing the oboe, her own struggles to breathe and stay calm during her illness, and her father’s dying breath.

As it turns out, it was written by Mimi Dixon, maiden name Still, daughter of the late Ray Still, principal oboist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for forty years (1953-1993). In this moving essay, she writes about her father, his last days (he died in 2014), the book they were writing together, and her own battle with leukemia. The breath itself is a point of meditation, as well as a device for exploring the powerful presence of her father. Wind and breath weave in and out of stories about her father’s approach to playing the oboe, her own struggles to breathe and stay calm during her illness, and her father’s dying breath. She writes, “My father loves singers, absorbs their wisdom about the secrets of the breath, ways to achieve resonance, ease, head tones. The ways they’ve outwitted the body and its limits, so that technique becomes pure music.” She goes on to share how her father thought about oboe technique, and how he taught his oboe students to tell themselves “oboe lies,” tricking the body into being more comfortable. And she has certainly written the most poetic description of a gouging machine and other reed-making devices that one can ever hope to read! Dixon deftly links the relaying of that more technical information with lyrical passages, like one that describes the insects that arrive in her garden on the wind, and another that rubs up against John Donne’s Holy Sonnet. “At the end of this world, will we rise up, inspired and inspirited? But art is the the only true resurrection I know,” she says.

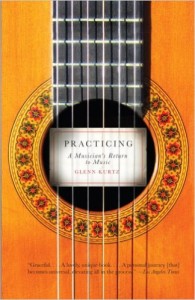

She writes, “My father loves singers, absorbs their wisdom about the secrets of the breath, ways to achieve resonance, ease, head tones. The ways they’ve outwitted the body and its limits, so that technique becomes pure music.” She goes on to share how her father thought about oboe technique, and how he taught his oboe students to tell themselves “oboe lies,” tricking the body into being more comfortable. And she has certainly written the most poetic description of a gouging machine and other reed-making devices that one can ever hope to read! Dixon deftly links the relaying of that more technical information with lyrical passages, like one that describes the insects that arrive in her garden on the wind, and another that rubs up against John Donne’s Holy Sonnet. “At the end of this world, will we rise up, inspired and inspirited? But art is the the only true resurrection I know,” she says. I have read a fair amount of musicians’ biographies and memoirs over the years, though not so many recently, as my curiosities and interests often take me far from music. A couple months ago, however, someone recommended to me a memoir by Glenn Kurtz called

I have read a fair amount of musicians’ biographies and memoirs over the years, though not so many recently, as my curiosities and interests often take me far from music. A couple months ago, however, someone recommended to me a memoir by Glenn Kurtz called